Search as you will but no written records can be found of the ghastly secret of the old Le Pretre mansion in the New Orleans French Quarter.

There is a good reason to believe that New Orleans authorities decided it would be advisable to destroy the reports both of the police and Harbormaster, Armand Ravenal following the discovery of the several headless bodies. Nevertheless, the story which quickly sped throughout the French Quarter is well known to many present day residents, especially to Robert Pretre, the prosperous Creole merchant in whose home the multiple murders took place.

Late one November evening in 1872, M’sieu Le Petre received a strange unexpected visitor in his house. The foreign looking visitor with a luxuriant black mustache wearing European clothes and a red fez adorned with a black tassel introduced himself as Hamid Pasha and stated his business in slow and hesitating French. He explained that he had been sent by an unnamed Turkish personage who wished to sojourn in New Orleans for an indefinite period. He was sent in advance to seek a suitable residence for the anonymous personage and his entourage. The Le Pretre mansion fulfilled the requirements satisfactorily, and therefore the M’sieu would have to vacate the place for a period of six months for a generous rental fee.

Not a person who would reject any opportunity to make money, Le Pretre was interested indeed. The deal was closed and Hamid Pasha immediately paid an amount three times greater than Le Pretre’s asking price. The owner and his family promptly departed on a long visit to relatives in Paris.

Weeks later, a mysterious ship flying a flag with a star and a crescent docked on the Mississippi harbor of New Orleans. Muted drum rolls could be heard marking every half hour of the watch. Curious spectators on the waterfront speculated that it belonged to a Turkish merchantman, judging by the ship’s design, flag, and drum rolls they heard rather than the traditional clanging bells. On the first day of docking, no sign of activity was seen except for the occasional appearance of a sailor upon her deck. Later in the afternoon Hamid Pasha went aboard.

That night, the Turkish ship stirred to life. Hamid Pasha was seen talking with a plumpish man in oriental garb. There were young, finely shaped female figures clad in flimsy pantaloons and open bolero vestees seen gracefully moving around the deck. Their golden earrings, jeweled rings, necklaces, wrist and ankle bracelets glistened In the brilliant moonlight.

The following morning, Hamid Pasha and the ship’s captain, Mustapha Bahan were rowed ashore. They first made a formal call to the office of Harbormaster Ravenal. This was customary for the masters of newly anchored vessels. Less understandable was a second formal call that lasted several hours, this one to police headquarters.

The reason became apparent later in the day when a number of policemen arrived at the waterfront and formed a cordon to prevent anyone from approaching too closely to the pier. Hamid Pasha, Captain Bahan and Harbormaster Ravenal next appeared and waited in silent expectancy.

By this time those in the vicinity of the waterfront realized that something most unusual was happening and a crowd gathered. Held back by the police the cordon opened only to permit several carriages, followed by empty drays to approach the pier. A boat, rowed by four sailors, was put out from the Turkish ship. Seated in the stern on silken cushions was a plumpish man, who at closer range revealed a young and unsmiling face.

A second boat was rowed toward the shore containing four females, veiled to the eyes. They were draped in robes that did not entirely conceal the fact that they were young and superbly formed. A third boat followed. In it were three more females and a giant black man, bare to the waist and resting the blade of a formidable scimitar across his heavily muscled arms.

They were all escorted to waiting carriages. The crowd gaped in awe as the exotic procession headed towards the Le Pretre mansion. The procession was followed by chests so heavy that the Turkish seamen who carried them, staggered under their weight when they were unloaded from the small boats and carried to the drays. These were thought to contain gold and precious jewels. Next came numerous trunks and other baggage. Finally came crates and barrels of food in a seemingly unending stream.

When the plumpish man and the females entered the Le Pretre residence, it was the last time they were ever seen alive.

Word got out that the man was Mejid ul-Aziz, a younger brother of the Sultan of Turkey. The harem he brought with him to New Orleans was completely isolated and guarded as if its occupants had remained in a Turkish palace.

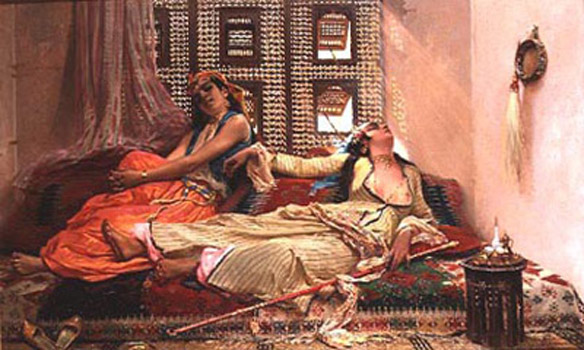

Many rumors circulated as to what went on behind the locked door of the mansion. It was whispered that the harem girls were heathens who knelt and prayed before images; that they bathed in sweet-smelling liquids; that servants and the giant black guard remained ever near them; that they rested on soft silken cushions awaiting the pleasure of their master.

Many rumors circulated as to what went on behind the locked door of the mansion. It was whispered that the harem girls were heathens who knelt and prayed before images; that they bathed in sweet-smelling liquids; that servants and the giant black guard remained ever near them; that they rested on soft silken cushions awaiting the pleasure of their master.

Sometimes passersby heard strange-sounding music and light laughter behind closely shuttered windows. Sometimes, on the rooftop, neighbors caught glimpses of one or more of the harem girls. Young, the neighbors said, with long hair the color of a raven’s wing and lips of brilliant red.

Some curious residents of the French Quarter tried to get inside the house by making formal calls. But Mejid ul-Aziz was not interested in their neighborliness or hospitality. At the front door, repeated knocks brought no response. At the rear, a servant would only shake his head and quickly close the portals.

From time to time one of the women of the household, veiled to the eyes, went to the market to shop. Whether she was a servant or one of the ladies in the harem there was no telling. She never spoke. She indicated what she wanted by pointing her finger; some rare fruit perhaps, or a particular kind of fish.

The purchases were paid for by the huge guard who always accompanied her, carrying a large market basket. Usually when attendants in the stalls spoke to him he merely shook his head as though he did not understand. On a few occasions when they persisted he opened his mouth and pointed to where his tongue should have been. It had been cut off at the roots.

Much of the food periodically was brought ashore from the Turkish ship, which remained anchored in the harbor. No one was permitted aboard nor did any of the officers or crew go ashore except such times as they rowed supplies to the waterfront and loaded them on the drays. They were a grim, uncommunicative lot.

With the passing of time the French Quarter remained curious, but gradually came to accept the mystery tenanted in the Le Pretre mansion. As far as is known, there was only one incident prior to the grim finale. A swashbuckling young Frenchman, Louis Malverne, had a reputation for being a daring Lothario, vowed to some of his drinking companions that he would meet one of the ladies of the harem.

A few mornings later he was found lying unconscious on Bourbon Street not far from the Le Pretre mansion. Recovering he, said that he had climbed one of the iron lacework columns supporting a balcony, opened an unfastened shutter and entered a room where he encountered one of the harem girls seated cross-legged upon a carpet and playing a musical instrument. She was not only unveiled but almost nude, scantily attired in gauzy pantaloons of some transparent material.

She was young. Malverne, added a girl of exotic and breathtaking beauty. She looked up at him and a startled cry escaped from her lips. This was all her remembered for it was then he was struck heavily from behind. After that, no one else tried to enter the house. The experience of Malverne proved that a day and night vigil was maintained within. He was considered fortunate to have been ejected alive.

Four months time went by. When one morning the waterfront discovered that the Turkish ship was gone. Cloaked by the starless darkness of the night; she weighed anchor and had been silently towed from the harbor by her crew in small boats, straining at their oars.

The following afternoon a middle-aged resident of the French Quarter, Mrs. Olivia Clairborne, who lived in a house diagonally across the street from the LePretre mansion, went out on the second story balcony prepared to enjoy her usual nap.

She glanced down upon the serenity of the French Quarter. In the bright sunlight she observed a thick red line that had coursed into the street from under the front door of the Le Pretre residence.

Mrs. Claiborne called her husband and he, too, stared. “Blood!” he said. The police were summoned. They knocked at the front door, received no answer and knocked at the back with the same result. They decided to break the door open when they discovered that its massive lock had already been forced and it yielded readily to a push.

Entering the servants’ quarters in the rear, they found no sign of disturbance. The great hallway and dining salon beyond likewise were dark and deserted. However, when they approached the front door they came upon the first body, that of the huge black guard. He had been slain on the spot where he had stood. His head and his scimitar were missing.

The police ascended to the second story. Where they found the bodies of the other occupants sprawled in ghastly profusion on divans, pillows, and carpets. From the front to the back of the house the floor was slippery with the blood of the corpses. There were eleven headless bodies; those of the master, Mejid ul-Aziz, his seven girls of the harem, and the three female servants.

No outcries or screams of alarm or terror had been heard during the night before. The murders unquestionably had taken place prior to the departure of the Turkish ship. They had been carried out quickly and expertly by several slayers. In addition, every trunk and chest in the house had been pried open and thoroughly rifled of the contents. Only a few jewels that had fallen behind one of the divans, had been left.

New Orleans authorities reasoned quite logically that the departure of the Turkish ship and the grisly massacre in the Le Pretre mansion were more than coincidence. They further reasoned that Captain Bahan and his crew, perhaps in league with the envoy, Hamid Pasha, had been the perpetrators.

But had their motive been robbery? If so, why had all the victims been decapitated and their heads taken from the house together with the treasures? Had it been because Mejid ul-Aziz stole the most beautiful women and the most priceless jewels of his elder brother and fled from Turkey to America, hoping to find safe refuge in New Orleans?

Had the Sultan wrathfully ordered the execution of Mejid ul-Aziz and his entire entourage—and commanded that their heads be delivered to him in proof that the deeds had been carried out? The residents of the French Quarter still believe so to this day.